By Rolando Garcia

Natural Sciences and Mathematics Communications

Houstonians may not feel it, but the ground beneath them is moving, and that could mean trouble for buildings or roads located on one of the hundreds of faults traversing the region’s surface.

Although geologists have long known of the existence of faults in Southeast Texas, only recently have University of Houston researchers produced a comprehensive map pinpointing the locations of the faults.

Using advanced radar-like laser technology, Shuhab Khan, professor of geology, and Richard Engelkemeir, a geology Ph.D. student, identified about 300 faults in Harris County. This information – the most accurate and comprehensive of its kind – could prove vitally useful to the region’s builders and city planners.

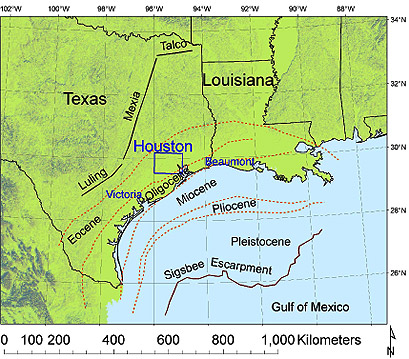

The shifting fault lines in Houston are not the kind that wreak havoc in earthquake-prone California. These faults, which originated millions of years ago during the formation of the Gulf of Mexico, can move up to 1 inch a year.

That may not seem like much, but such movement over several years can cause serious damage to buildings and streets that straddle a fault line. And for those structures that are on the subsiding side of the fault line, the lower elevation could make it more susceptible to flooding.

Khan and Engelkemeir, who published their findings in the February issue of Geosphere, began by looking at data compiled during a 2001 study funded by the Federal Emergency Management Administration and the Harris County Flood Control District. That year Tropical Storm Allison dumped nearly 40 inches of rain on the Houston area over five days. The storm caused nearly two dozen deaths and billions of dollars in property damage.

To update floodplain maps, FEMA and the flood district employed lidar technology to survey the topography and elevation of the county. From an aircraft flying overhead, laser beams were directed toward the ground. The time between the laser beam pulse and the return reflection from any given point on the ground can be used to determine the distance between the instrument and that point on the surface.

Buildings and vegetation are then removed from the model to produce a map that records even the most subtle elevation differences on the surface.

Khan and Engelkemeir pored over the data, refining the grids to identify more than 300 faults. Many were associated with the salt domes in the southeast part of the county. Others were located in the northwest portion of the county near Highway 6 and Interstate 10, where there is ongoing subsidence, Engelkemeir said.

During the summer of 2005, Engelkemeir personally visited about 50 of the faults he located with the lidar data looking for signs of deformation and displacement where the land on one side of the fault was rising over the other.

At many of the faults, Engelkemeir saw cracks in street pavements. Residents living nearby reported foundation problems, and at one home there was 1 meter of displacement between the garage and the house. At another site a building had been so damaged by ground shifts it was condemned.

Geologists are still studying what causes fault movements in the region, with some attributing it to groundwater and petroleum withdrawal, Engelkemeir said.

Khan is now turning his attention to Fort Bend County. Using lidar data, Cecilia Ramirez, a master’s student working under Khan, has found one potential fault near the Brazos River levee.

By knowing the location of surface faults, builders and government planners will be able to avoid those areas or accommodate potential ground shifts in their construction plans, Khan said.

He also cautioned that although lidar has allowed the researchers to identify previously unmapped faults, there might still be faults in the region that have yet to be located. |